Rapid Prototyping Struggles to Find Niche in Art, Design

Despite slow and steady adoption in the industrial sector, rapid prototyping in art objects and household decorative design has been disappointing. Design products manufactured using additive fabrication technologies still pale significantly in contrast to the material variety, finish, and the low cost of products made using traditional methods.

Some in the design business attribute the glacially slow transition to layered manufacturing to simple lack of maturity in the technology. “People

in the RP industry sometimes seem to me a little blinkered about how limited the available materials and quality are,” says artist Bathsheba Grossman by email. “One has only to look around a room to observe that most artifacts are made of materials not accessible to RP, with finishes and quality beyond anything it can achieve, at prices that are dirt cheap by comparison.”

Quin Lamp

Photo courtesy Bathsheba Grossman

“So even though RP will to some extent create its own sphere of objects,” she continues, “I feel like there's a long haul before it can compete in the popular mind with ‘straight’ production techniques in plastic, glass and metal, let alone wood and textiles. I think an art buyer who doesn't care about the technology for its own sake, and just wants a wonderful object, does better overall looking at a mature craft such as art glass or stone carving. So barring quantum leaps in the technology, I predict slow growth among hardcore early adopters for quite a while to come.” Grossman is no idle observer – she was one of the earliest adopters and biggest proponents of digital design and 3D rapid manufacturing for design products.

Others in the business attribute the sluggish technology adoption not to the traditional bogeyman of high costs, but to inertia factors and consumers’ narrow self-interest. “Yes our products are still more expensive on the retail level,” admits RP designer and entrepreneur Janne Kyttanen, “but think how the entire planet is wired around a mass production infrastructure, which has been created over the last 200 years. A lot of countries are being exploited in this and eventually we will pay the price in cleaning this mess…our oceans, environments, air, planes crashing into buildings etc., but nobody stops to calculate how much this actually costs all together. Which is cheaper?”

Kyttanen exchanged emails with RapidToday from Europe, where he established FOC (Freedom of Creation) in his native Finland in 2000 (from 2006 it has been based in Amsterdam, The Netherlands). FOC specializes in design for rapid manufacturing of interior products and accessories.

FOC has had to exercise a combination of right-brain creativity and left-brain technology development. In 2005 FOC launched a line of EOS laser-sintered clothing, a technique it has pioneered. For now, the plastic-chain-linked clothing is nothing more than a novelty, as traditional textiles can be manufactured for a small fraction of the cost. “Textiles are not going [well] at all, because the entire textiles industry is based on a meter price. Our stuff is just powder,” says Kyttanen.

Not to say that FOC isn’t prospering. “Lights are going really well,” says Kyttanen. For most RM design outfits, light fixtures and shades dominate. “Consumers are accustomed to paying high-design prices for lamps, and that makes the niche accessible,” explains Grossman. “There are many small household products which could be more interesting with RP – direct metal is an obvious fit with cabinet hardware, kitchen gadgets, doorknobs and finials, and so forth – but there's less culture of name-brand design surrounding these things, so it's harder to hit a price point that makes sense.”

Thus most of the additive fabrication design objects have been lights, many of them stunning:

· Designer Alexander Lervik of Sweden used a MRI scan of his own head to create a surprisingly attractive 3D-printed MYBrain table lamp.

· Designed by artist Assa Ashuach, and made by London-based Complex Matters, the EOS laser-sintered AI (artificial intelligence) light changes shape and varies its intensity based on five sensor inputs.

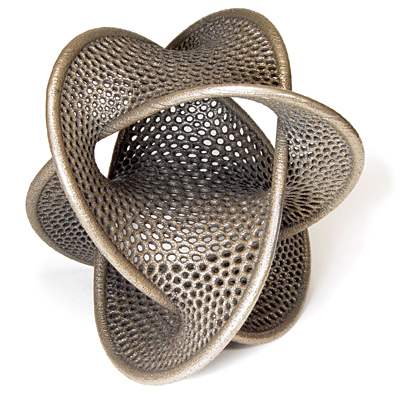

· Bathsheba Grossman made Time Magazine’s 100 most influential designs of 2007 with her Quin lamp. The 9” diameter dodecahedron-based lamp is made by Materialise.MGX and retails for US$2,099. About 150 are sold annually.

Operating out of California, Grossman is one of the world’s top 3D printing artists, specializing in math models and sculptures and 3D laser-etched glass. Grossman runs Bathsheba Sculpture LLC, one of the few RP art sites that has an e-commerce functionality – you can actually buy rapid-manufactured art from her site. The site registers sales of up to US$500,000 per year of art. The most popular (“The 120-Cell” and “The Gyroid” math models; “Quintrino” and “Nexus” sculptures) sell at the annual rate of 30-40 for the full size, and 100-150 for the “minis.”

Grossman, for one, is not awed by the technology. From her website: “I use a lot of technology…This isn't because I love gadgets; it's much

more trouble and expense to use new media instead of the more mature techniques that most sculptors enjoy. I do it because the shapes I have in mind aren't moldable [due to undercuts], and I want to make a lot of them…Ordinary sculpture technology just does not do the job.”

Laser-Sintered Polyamide Bag

Photo courtesy FOC

For digital designing, Grossman uses the 3D modeling program Rhinoceros the most. Once she has a design she likes, she transfers the file to the ProMetal division of ExOne. There, the STL file is downloaded to a machine, where stainless steel powder is held together using a laser-activated binder in about .15mm thick layers. After the model is fully built, it is placed in an oven, where the binder is driven out and the steel is sintered into a 60 percent dense object. To reach full density, the part is infiltrated with liquid bronze material. A few traditional finishing steps by Grossman, and the artwork is ready for sale. The final product is gallery quality, at prices that make the art accessible to middle-class buyers.

Still, Grossman doesn’t harbor any illusions about whether she’ll ever be able to compete with Target designer Michael Graves on price. “Cost comes from the scarcity and immaturity of the technology, and it'll go down only as the tech and the market mature,” she says. “The hardware business cycle moves slowly. We're all accustomed to the way the software business moves, just a few years or even a matter of months from invention to trend to explosion to universal, but manufacturing doesn't do that. It takes many years.”

As product size and prices rise, the market for standard RM objects and accessories is significantly curtailed, unless consumers see additional value in the product. The answer is to deliver that value – and exploit one of the primary benefits of additive fabrication – by delivering one-of-a-kind products that are designed by the customer himself. The attraction will be strong, says designer Kyttanen, using his printed clothes as an example. “I think it is about the options you have,” he says. “You don’t have to cut your garments into pieces anymore and then sew them together. You can add clicks, snaps, zippers, etc. and print them at once. This is very disruptive for the textile people, who don’t yet understand that one day the needle and threat might be obsolete.”

Many think that a product like this can demand a real premium. As an added bonus, the increasing problem of cheap knock-offs becomes a non-issue.

One proponent of this mass customization or mass individualization is artist Lionel Theodore Dean of FutureFactories. As part of his practice-based PhD study at the University of Huddersfield, Dean has worked on commercial systems for the creation and marketing of individualized products like candlesticks, furnishings, and lighting. From Dean’s website: “Instead of creating a single design solution, the designer creates a template, which establishes a series of rules and relationships that potentially allow an infinite range of outcomes.”

Traditionally, the tools required to engage in digital design and manufacture have had steep learning curves, discouraging all but the most determined and technologically-savvy. Artist Grossman says that better software and three-dimensional interface devices would help, but that there are other factors at play as well.

“I'm not sure there's a huge amount of back pressure here,” she says. “If one looks at the graphic arts in relation to cheap image manipulation software and digital photography, those things lowered the barrier to becoming an image artist, and certainly more people do that type of work now than before, but it didn't turn vast swaths of the population into artists who weren't interested or lacked talent in the first place. I think that'll be even more true of 3D. I'm guessing that the difficulty of inventing and designing satisfying 3D objects is present in the problem itself, rather than being an artifact of problems with the tools.”

Some companies are starting to test this theory by taking simple digital design and manufacture direct to the masses. So far, consumers don’t need anything more than a keyboard and a mouse, nor much in the way of design ability. Some of the players in this niche:

· Fabidoo – German outfit offers unique key rings (US$15-31) or 1GB USB flash drives (US$31), using blank or user-generated templates. Product is built using plaster powder and resin infiltration, then covered with a glossy surface finish.

· Shapeways – Calling itself an online consumer co-creation community, this Dutch company is currently in private beta. Accepting STL, Collada, and X3D formats, Shapeways provides a real-time cost estimate. Available technologies are SLS, FDM, and Objet.

· JuJups – A subsidiary of Genomtri, a Singapore-based software producer, the company offers customized picture frames (US$15). A Z Corporation 3D printer builds frames with user-specified shapes, colors, and messages on them.

· Zapfab – UK-based firm provides a forum for creating, sharing, modifying and 3D printing (Z Corp.) digital designs. Still in alpha stage, designs are relatively expensive with below-average utility or artistic merit.

· Ponoko – Based in California, this company allows customers to buy or sell jewelry mostly. Wood and acrylic items are manufactured in San Francisco and New Zealand using laser cutting. Has plans to add 3D printing and CNC routing capability.

Of course, the ultimate goal of many fab fans is a desktop fabber in every home – aka personal desktop manufacturing. Designer Kyttanen

thinks this reality isn’t so distant, on cost factors alone. “Which is more expensive?” he asks. “You buying a 3D printer at home, downloading files from the ‘net and producing things yourself, or you getting into your car, driving around town searching for things, never being able to find exactly what you want. People don’t seem to look at the bigger picture, but purely the price tags on products. Even if things were then more expensive to produce at home, at least people would get exactly what they want.”

New Borromean Rings Math Model

Photo courtesy Bathsheba Grossman

Grossman, on the other hand, thinks the rate of adoption of 3D printing in design will continue to be sloth-like due to ongoing limits of the technology. In fact, the Queen of RP is exploring – gasp – injection molding for her next set of projects. “The experience of designing for RP has led me to think about overlooked possibilities in traditional manufacturing, and also to a greater interest in mass production using mature technology,” she says.

Additional Resources:

Part of the big Materialise Group headquartered in Belgium, .MGX was founded in 2003 and is one of the leaders of what it calls the “growing smart luxury market” of direct digital manufacturing of designed products.

Swedish design group pioneered Sketch Furniture, which uses motion capture to record pen strokes made in the air. The resulting 3-D patterns are built by a laser sintering machine. Furniture costs about US$10,500 per piece.

California service bureau that specializes in printing toy sculptures and small works of art.

Milan, Italy-based lighting and furniture manufacturer that started rapid manufacturing lamps in 2006. Produces laser-sintered Entropia, designed by Lionel Dean of FutureFactories.

A spin-off from University College London, the company was founded by Siavash Mahdavi. Besides designing custom materials and structures, Complex partners with artist Assa Ashuach; products have included the SLS-produced Osteon Chair and AI Stool.

Created in 2005, the conference and exhibition examines the role of software and generative strategies in art and design.

Offers 3D color prints of World of Warcraft characters or avatars. The up-to-203mm-tall custom statues are US$130 in North America.